Here’s why there are no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ drugs – not even heroin

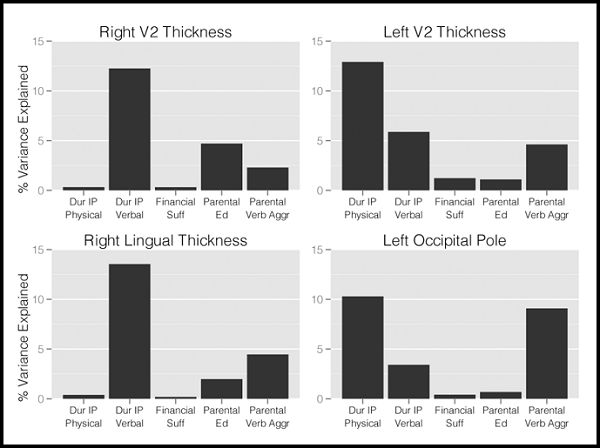

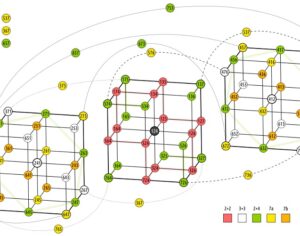

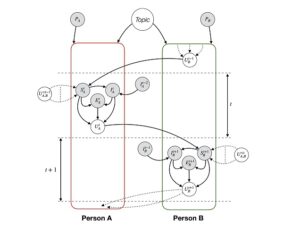

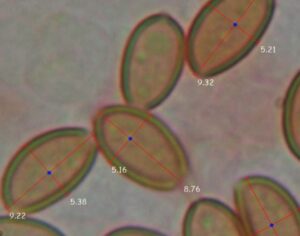

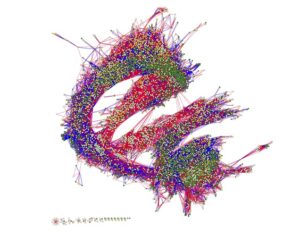

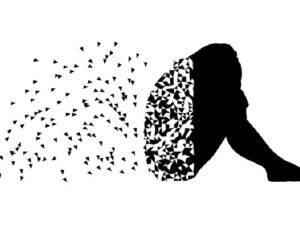

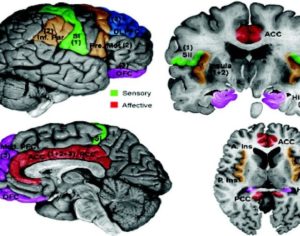

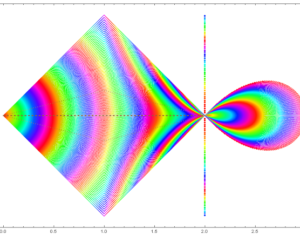

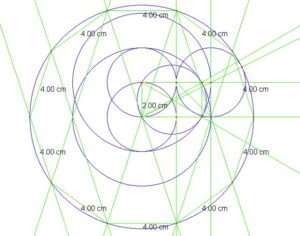

*Linear regression with variance decomposition indicating the percent of variance in adjusted regional cortical thickness measures from FreeSurfer accounted for by regressors. Dur IP Physical – duration of witnessing interparental physical aggression (years), Dur IP Verbal – duration of witnessing interparental verbal aggression without physical violence (years), Financial Suf – perceived financial sufficiency during childhood, Parental Ed – average parental education (years), Parental Verb Aggr – average parental verbal aggression score.

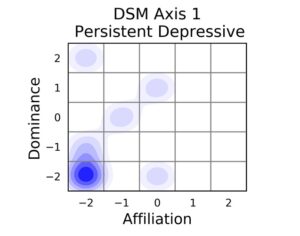

Before she found heroin, Allison could not get out of bed most mornings. She contemplated suicide. She saw herself as “a shitty lazy person who felt like crap all the time”. She was deeply depressed, and no wonder. As she explained in an interview with NPR last month, in slow, halting sentences, she’d been molested by three family members by the age of 15. One of the three was her father.

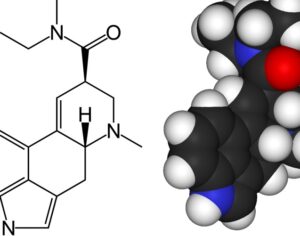

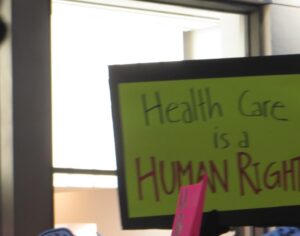

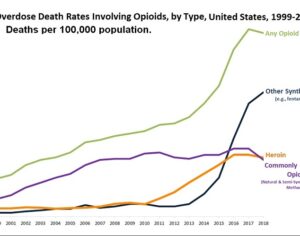

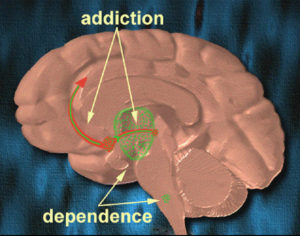

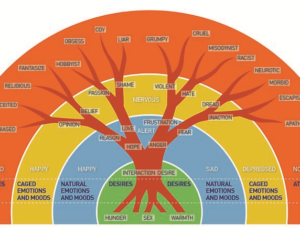

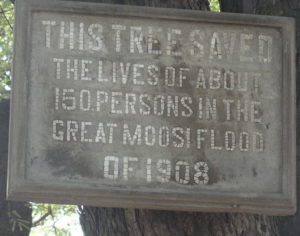

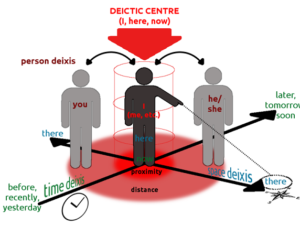

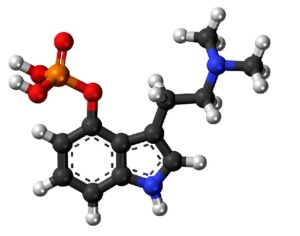

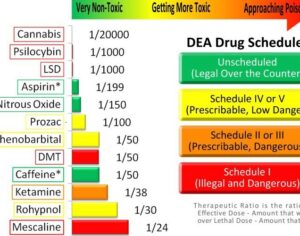

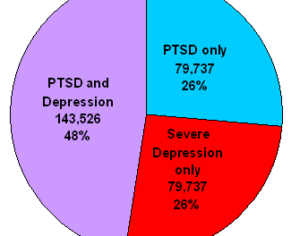

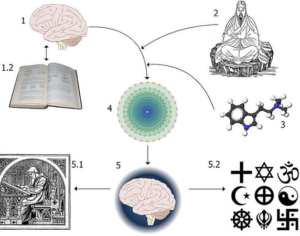

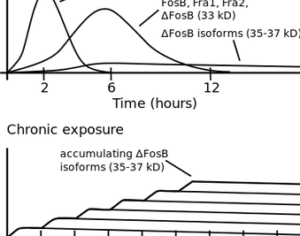

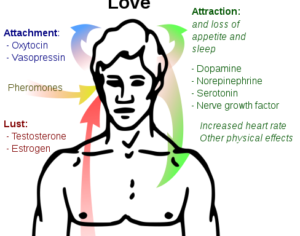

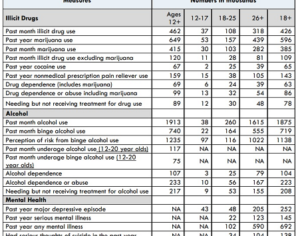

For Allison, the good was undeniable. Heroin helped her overcome a depression that very likely arose from her history of sexual abuse, a trauma that left PTSD in its wake and drained her life of joy, functionality, and any semblance of normality. Allison represents the rule rather than the exception. PTSD often triggers anxiety and depression, and substance abuse is as high as 60–80% among those with PTSD. In fact, the largest epidemiological study ever conducted found an extremely strong correlation between the degree of childhood adversity and injection drug use. When Allison got tired of heroin, she was able to quit, as most addicts eventually do. She found a psychiatrist and learned to live without it, though she reports that she continues to rely on antidepressants. The point is that, for her, heroin was an antidepressant – a very effective one. It shouldn’t be surprising that a powerful opiate can help people overcome psychological pain. Opioids are critical neurochemicals, helping mammals to function in spite of pain, stress and panic. Rodents play and socialize far more easily after being given opiates. Opioids are even present in mother’s milk: they are nature’s way of ensuring an emotional bond between infant and mother. Opiates might be too attractive for some people some of the time; obviously addiction is a serious concern. But that doesn’t make opiates intrinsically bad. The failure of the “war on drugs” should help us recognize that people will never willingly stop taking drugs and exploring their benefits and limitations. It’s ridiculous to deal with this human proclivity by labelling most or all drugs as “bad”. And it’s absurd to mete out punishment as a means for eliminating the drugs we don’t like. Instead, let’s expand our knowledge of drugs through research and subjective reports, let’s protect ourselves against the dangers of overdose and addiction, and let’s improve the lives of children raised in ghastly circumstances.

Original Article (The Guardian):

Here’s why there are no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ drugs – not even heroin

Artwork Fair Use: Tomoda A, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Teicher MH (2012)